S

Subhash Kak

Guest

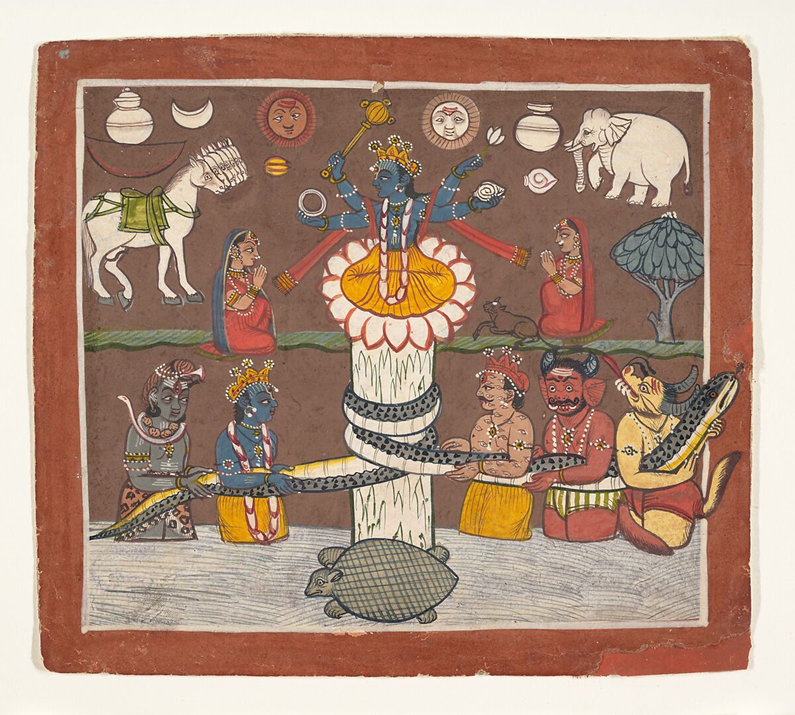

Churning of the Ocean, Mandi, (c. 1790), Metropolitan Museum

The story of the Churning of the Ocean (samudra- or amṛta-manthana) goes to the very heart of Hinduism. It is found in various versions in the Purāṇas, the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahābhārata, and is referenced in the Vedic hymns. It is a story about the very nature of being and the origin of creativity.

Reality is One, but it gets projected in the binary of the material world and consciousness. The physical world goes through continuous change and its embodients have finite life for they are part of birth and death. Consciousness, on the other hand, is known to us in its intimations from time to time in our senses that appear as points of light (div = shining), from which the word deva, god or divinity arises.

In our dichotomous existence, we dance between the poles of consciousness and the body. If the devas are the cognitive capacities that relate to consciousness, the asuras represent senses bound to physicality. The asuras are also called daityas, for they are the children of Diti, Finitude, who believe only in the body and its finite life, whereas the devas are the children of Aditi, Infinity, which symbolizes consciousness that is transcendent and boundless. In traditional translations, the devas are the gods and the asuras (daityas) are the demons.

The devas and the daityas are constantly in struggle, for we can’t make up our mind whether we are the body or the self that resides within it. The body is substantive and the sense of self elusive, so in personal experience — as in mythic time — the devas often find themselves weaker than the asuras.

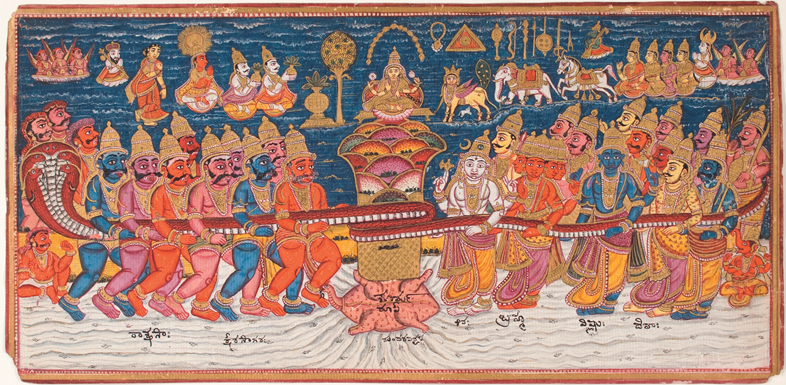

The Ancient Text of the Lord Creation (c. 1825) Edwin Binney 3rd Collection-The San Diego Museum of Art

In one of their fights, the devas are defeated and exiled. In despair, they go to Viṣṇu, who is the Lord of Existence. He tells them that to improve their situation they should obtain the elixir of immortality (amṛta) for which they will first have to make peace with the demons and jointly churn the waters (samudra manthana) of the Cosmic Ocean of Milk.

The devas plead with the demons for truce and it is decided that Mount Mandara, near Kailāsa at the eastern quarter of the Meru Mountain, will be used as the churning rod and Vāsuki, a snake residing on Śiva’s neck, will be the churning rope. Mt. Mandara is Mt. Merumandara, the axis of the embodied universe, and since Siva represents consciousness, Vāsuki is the agent by which it is awakened in embodiments.

At the cosmic level, the ocean is the Milky Way, and the churning is the precession of the earth’s axis, which brings about new ages that lead to evolution of life forms. At the personal level, the churning is between the polarities of body and consciousness in the movement of the breath. The churning is the tapas that underlies one’s sādhanā which is explicitly entered into in various modes of Yoga and Tantra.

In Tantra literature, Meru is the spine connecting the mulādhāra, a four-leaved lotus at the base, with the sahasrāra, the thousand-petalled lotus at the crown of the head. The mulādhāra is the primary consciousness of the body whereas the sahasrāra is the doorway to transcendent consciousness.

The union of the two lotuses represents the merging of the light of consciousness (Śiva) with embodied reality (Śakti). This union leads to freedom, and that is also a rebirth actuated by the amṛta permeating the entire being. If Mt. Mandara is the suṣumṇā nāḍī, the serpent rope is made up of the two side nāḍīs called iḍā and piṅgalā.

In the cosmic drama, Viṣṇu’s mount Garuḍa carried Mt. Mandara to the midst of the ocean and Vāsuki coiled himself around it. Viṣṇu counseled the devas to hold the head of the serpent and the asuras the tail, but the asuras refused finding that to be inauspicious. The devas relented and held the tail henceforth and the churning commenced. However, Mandara was too enormous and began to sink to the bottom of the Cosmic Ocean. In response to their cries of anguish, Viṣṇu, assuming the avatāra of the tortoise (kūrma), entered the waters and supported the mountain on his back.

The gods and the demons gathered various herbs, and threw these into the water. As the churning began, the choice of the demons to be on the side of the head of the serpent didn’t turn out too good, for noxious fumes from the mouth of the serpent weakened them and the gods were invigorated by the rainclouds blown towards the tail by the fumes.

From this venom developed the deadly poison halāhala or kālakūṭa, threatening the existence of humanity, gods and demons.

The gods sought refuge at the feet of Viṣṇu, who in turn, invoked Śiva and offered prayers to him with hymns of praise: “O Lord, you are the chief of the gods, and should accept whatever is produced first from the churning of the Ocean. Kindly receive the poison as your gift, the tribute of the first offerings.” Śiva, moved by the words of Viṣṇu and grieved by the plight of the gods, complied with the request. He took the poison but held it his throat, which made it blue, which is why he is called Nīlakaṇṭha.

The halāhala poison is the sense of death (Yama, the Twin) that one must carry with one all the time if one is on the path of truth and self-understanding. This is the reason why one of the manifestations of Śiva is Mahākāla. To be truly alive, one must experience death.

As the gods and demons resumed churning, the churning rod began to sink into the waters of the Cosmic Ocean. Viṣṇu now helped with the churning while standing between the devas and asuras. He was thus in three roles simultaneously: holding up Mt. Mandara, helping with the turning, and at the top of the mountain being worshiped by the devas and demons.

After thousand years had passed, numerous things began to emerge from the ocean.

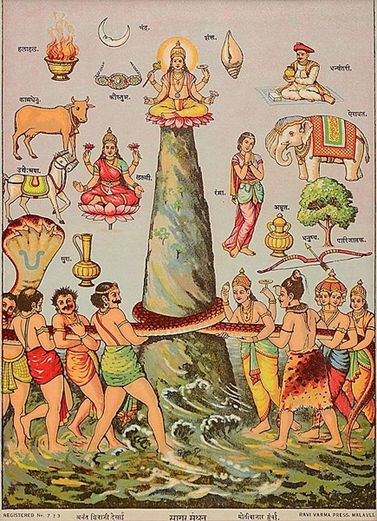

Nineteenth century painting of the treasures arising from the churning

Śrī or Lakṣmī: the goddess of prosperity, who chose Viṣṇu as her consort.

Apsarās: divine damsels who chose the Gandharvas as their companions.

Vāruṇi: the goddess of wine, who chose Varuṇa as her husband.

Surabhi or Kāmadhenu: the wish-granting cow.

Airavata and other elephants: taken by Indra.

Uchhaiḥśravas: the divine seven-headed horse, given to Bali.

Kaustubha: the most valuable jewel, claimed by Viṣṇu.

Kalpavṛkṣa: a divine wish-fulfilling tree taken to Indraloka by the devas.

Śāraṅga: a bow given to Viṣṇu.

Candra: crescent moon, claimed by Śiva.

Halāhala: the poison swallowed by Shiva.

Pāñcajanya: Viṣṇu’s conch, which produces the primeval sound of creation when blown

Jyeṣṭhā (Alakṣmī): the goddess of misfortune (who often accompanies fortune)

Finally, Dhanvantari, the heavenly physician, emerged with a pot containing the amṛta, the nectar of immortality. Fighting ensued between the devas and the asuras who took the pot from Dhanvantari and ran away.

The devas appealed to Viṣṇu, who took the form of Mohinī, a beautiful and enchanting damsel. The asuras were so overcome by her beauty that they quite forgot about the amṛta pot and handed it over to Mohinī. She made the devas and the asuras sit in two separate rows and began distributing the nectar among the devas first. An asura named Svarbhānu had disguised himself as a deva and drank some nectar. The deities of the sun and the moon, Sūrya and Candra, noticed this disguise and they informed Mohinī who, cut off Svarbhānu head with her discus. From that day, his head was called Rāhu and his body Ketu, which represent the ascendant and the falling nodes of awareness. When the nectar was emptied from the pot, Viṣṇu assumed his true form and departing to his abode.

Realizing that they had been deceived, the asuras re-entered combat with the devas. Rejuvenated by the amrta, the devas emerged victorious and exiled the asuras to the Pātālaloka (nether-lands).

Continue reading...