S

Subhash Kak

Guest

Photo by Jean Wimmerlin (Unsplash)

A generation ago, magazines and journals were full of dire warnings about runaway global population, a future of hunger and starvation for millions, and population-induced climate change that will worsen the problem of feeding humanity.

The reality has turned out to be different. The world population is decreasing in most parts of the world. There are scenarios that the population a hundred years on may only be one-tenth of what it is now. If this were to happen, the world will change in unimaginable ways: whole regions will be depopulated, current political systems will be replaced, and in a world with very few children, the idea of the family will disappear.

There are several reasons why population is falling. Technology has made birth control easy and artificial intelligence raises the spectre of machines replacing humans at virtually all jobs so that parents do not want to have children who will have dim prospects in life. With the breakdown of the extended family, taking care of the child for many working parents has become unaffordable.

There is also a deeper reason. If the same spirit is within each person, all humanity is family and the old idea of extending one’s biological lineage does not hold the power it did for earlier generations.

Falling fertility rate

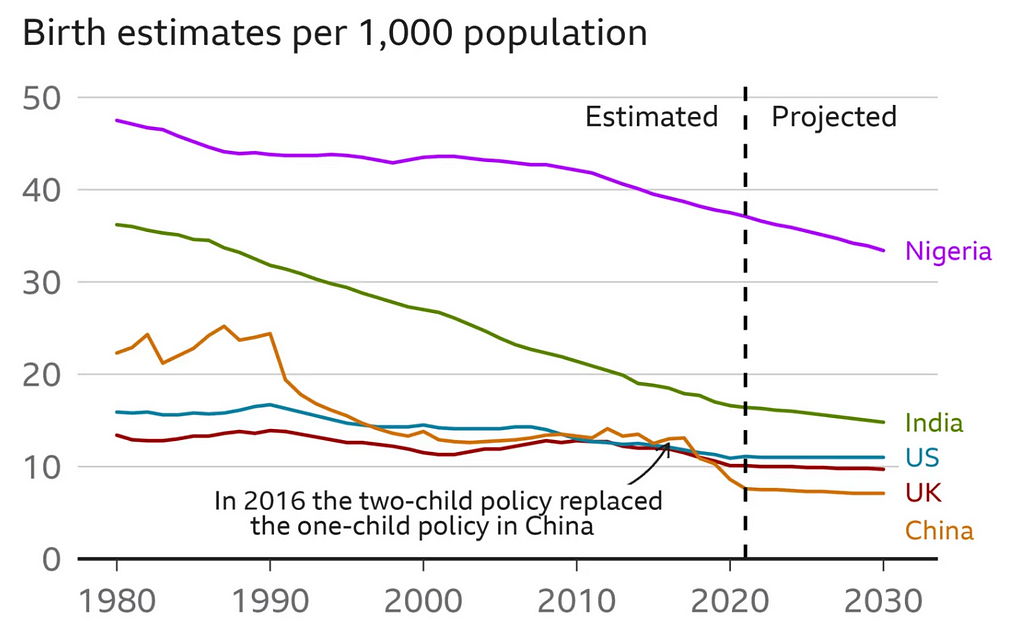

The total fertility rate (TFR) — the number of live children the average woman bears in her lifetime — has been falling since the 1970s. It has dropped under the 2.1 threshold (the “replacement rate,” to account for infant mortality and sex imbalances), below which the population will fall, in more and more countries. This decline in the fertility is perhaps the most remarkable trend of our times.

The decrease of the TFR below the replacement threshold of 2.1 has proceeded for over half century. In the US, the TFR fell below 2.0 in 1973, and in the UK, in 1974. In South Korea TFR was above 2.0 until 1984; in China until 1991. The fertility rate in Iran is 1.6 and in India it is 2.0.

South Korea’s current fertility rate is 0.68. This means that if the fertility rate doesn’t change across generations,100 Koreans will have 34 children, who in turn will have about 12, and in yet another generation it will be down to 4. In three generations (90 years), the survivors will be 34 who are 60-year-old, 12 who are 30-year-old, and 4 who are young. In another generation, the population will essentially be 16 of whom 12 are 60 years old and 4 are 30 years old.

Despite incentives to women to have more children, the South Korean fertility rate has kept on decreasing for the past 16 years. Demographers call it the “low-fertility trap” in which once a country’s fertility rate drops below 1.5, it is virtually impossible to turn it around. Incentives have also been tried by France, Australia, and Russia with similarly disappointing results.

Source: United Nations Population Division. This estimate tracks TFR

If the South Korean situation is an outlier, let’s consider Japan where TFR fell below replacement in 1976 and in 2008 the population began shrinking. It takes a generation after TFR falls below 2.1 for population to start tapering, and with another generation, the population collapse is in full swing.

Perhaps, the current Japanese fertility rate of 1.37, which has held steady for some time, is more representative of the world. So, 100 Japanese now will have 68 children. In the second generation, this will lead to 48 children, and in three generations to 33 children. Counting each generation to be about 30 years, the population of Japan that will have babies will approach 1/3rd of the current figure in about 90 years.

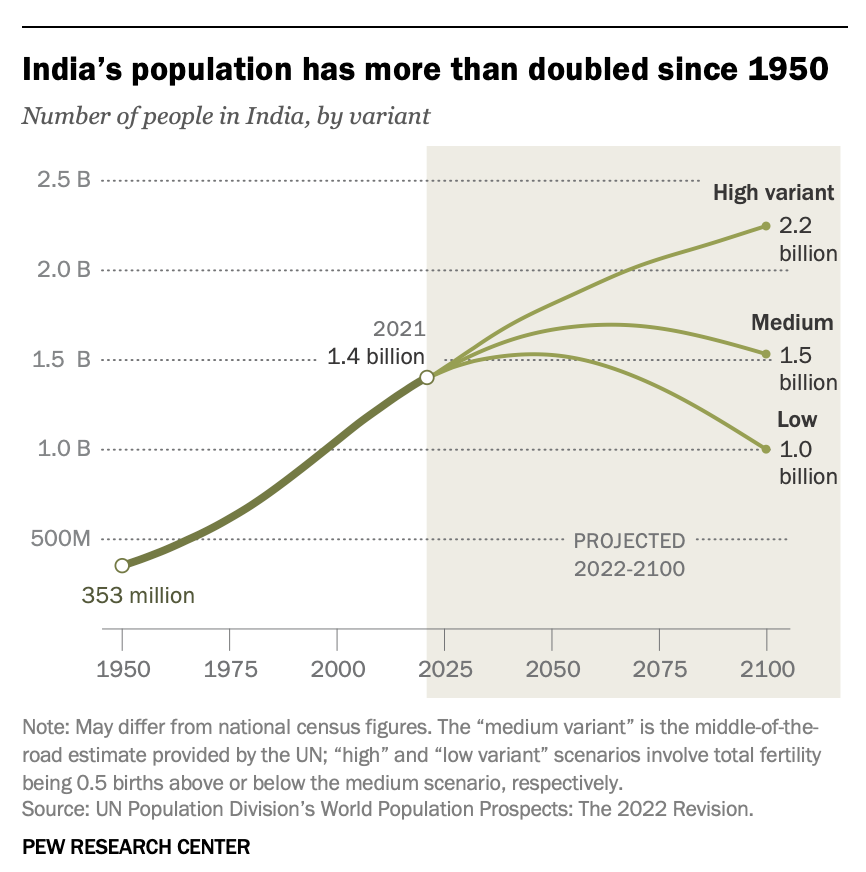

India TFR is currently 2.0 and in the low scenario, its population will shrink by nearly 500 million in the next 75 years. China could fall to 1.1 billion people in 2050 and 400 million people in 2100, which will be a loss of about a billion people in a mere 8 decades.

India will shrink by about 400 million people during the present century

Although sub-Saharan Africa fertility rates remain well above the replacement rate, even in this region the fertility is expected to fall rapidly. The global TFR, according to the UNPD’s medium-variant projection, will fall from 2.3 in 2021 to 1.8 in 2100; the more radical projections estimate the global population to fall to about 4 billion by 2100.

Another longer-term projection by Austria’s Wittgenstein Centre for Demography sees global fertility approaching 1.3 by the end of the 21st century, with male and female life expectancy both near 100, and the median age over 60. The population will fall to 250 million by 2200 and it will be under 100 million by 2300.

The lower estimates are more likely given the transformative power of AI

The future of society

Projections of future world population are based on assumptions on future mortality, fertility, migration, and other factors. One factor that has been left out is that of fundamental changes in society due to the permanent disappearance of jobs caused by robots and AI machines and the impact it will have on the human psyche. In my view, the AI factor points to an even more drastic population decline than forecast by demographers.

The fragmentation of the traditional family, pervasive voluntary childlessness, the rise in single-parent homes, and the new normal of co-habitation and unmarried motherhood has made child-rearing very hard. We live in the age of narcissism where people are not as much thinking about raising children in extended kinship networks as about personal fulfilment and sense-gratification.

In East Asia, more women are choosing to marry later or not marry at all. Many Japanese youths show no interest in sex. There is rise in co-habitation, but illegitimacy and single parenthood are severely stigmatized. Only 2% of births occurr outsid of marriage, compared to 30–60% of births in Europe and North America.

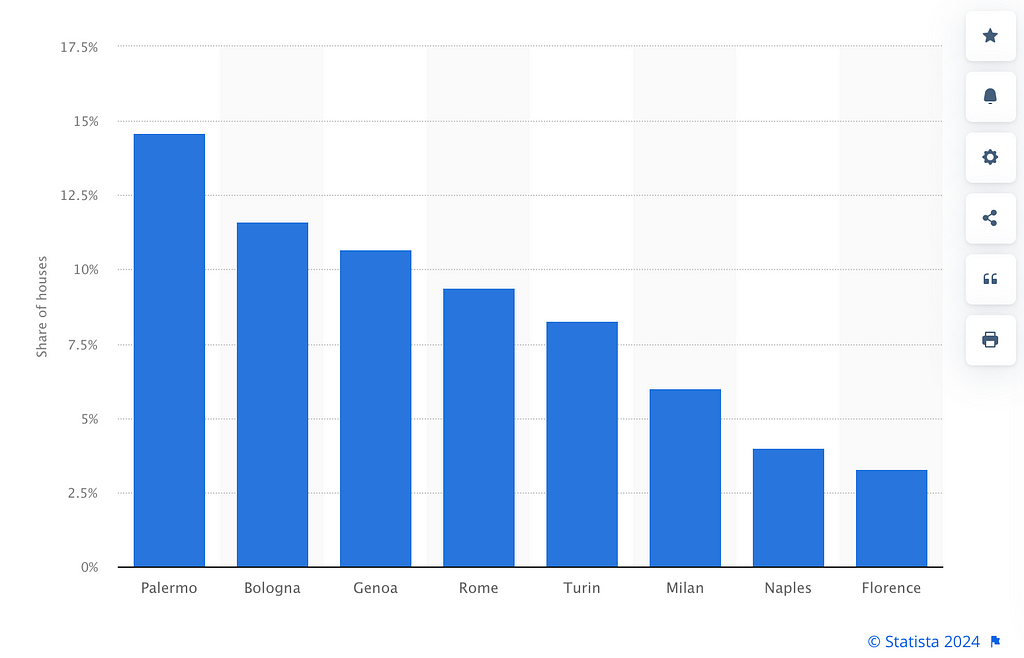

As populations shrink, the price of housing will fall. In Japan, the average value of real estate is less than half what it was in the 1980s and 1990s. There are more than 8.5 million akiya, or abandoned homes, in rural Japan; other estimates peg the number closer to 11 million. Spain has about 4 million empty homes, and the numbers in Italy are similar. This is the future for other countries as well.

Share of empty houses in the largest cities in Italy in 2018

As populations shrink, national retirement systems will become insolvent. Typically, pension systems take a portion of annual tax revenue and then distribute it to the retired people. This works fine when one has three or more working age person for each retiree, for one can tax one-fourth of the income and get three-fourths of one person’s salary to distribute to the pensioner.

But Japan is approaching one working age person for each pensioner and China will soon have one working age person for two pensioners, and clearly these ratios are unsustainable. The rest of the world will face the same problem soon.

The social compact on which modern political and economic arrangements rest is already facing severe pressures. As the population fall becomes extreme, current banking and political systems will be unsustainable.

Continue reading...