S

Subhash Kak

Guest

Lalitāditya’s Martand Sun Temple (photo by Varun Shiv Kapur)

Lalitāditya Muktāpīḍa (r. 724 –757 CE), “Pearl-crowned tremulous Sun”, of Kashmir’s Kārkoṭa dynasty was called a world conqueror and universal monarch by the 12th century historian Kalhaṇa in his Rājataraṅginī. Lalitāditya defeated the central Indian king Yashovarman, and then marched to eastern and southern lands, subjugating several more rulers on his way back. Later his campaigns towards the north and the west brought him further victories, and he conquered lands in the region of the Taklamakan Desert. Many scholars believe that Lalitāditya created an empire that included major parts of India as well as present-day Afghanistan and Central Asia.

Lalitāditya was also a great builder of cities such as the new capital Parihāsapura, temples, and vihāras. Many of his temples were dedicated to Vishnu, Rāma, Krishna, and Shiva, and there were stupas and vihāras to the Buddha. The great Sun-temple of Mārtanḍ, although in ruins now, is a testament to the grandness and beauty of his conceptions.

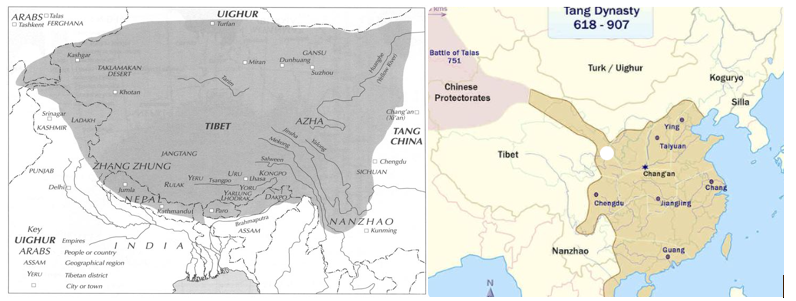

Tibetan empire at its greatest late 8th century & Tang empire protectorates north of Tibetan empire

Apart from Kalhaṇa’s account, Lalitāditya also finds mention in the New Book of Tang (Xin Tang shu), a record of the Tang dynasty of China. This text mentions him as “Mu-to-pi” or “Muduobi” (a variation of Muktāpīḍa). The 11th century Iranian chronicler Al-Biruni mentions a Kashmiri king called Muttai, who was most certainly Lalitāditya (from “Muktāpīḍa”), and further claims that the people of Kashmir organized an annual festival on the second day of the Chaitra month to celebrate Muktāpīḍa’s famous victory over the Turks.

The Kārkoṭa dynasty

Lalitāditya was the youngest son of the Kārkoṭa [1] king Durlabhaka and queen Narendraprabhā, who was previously married to a foreign merchant settled in Kashmir. His two older brothers who preceded him as king were Candrāpīḍa (r. 712/3–720) and Tārāpīḍa (r. 720- 724). Although Kalhaṇa says that Lalitāditya’s reign lasted for over 36 and years, there is other evidence that suggests that it was c. 724 — c. 757 CE.

There is an interesting backstory to the links between Kashmir and rival Tibetan and Tang empires during the years before Lalitāditya’s ascension to the throne. A Kashmiri envoy was at the Tang court, and we have evidence that the Tang envoy to Kashmir in 720 reciprocated with honors to “King Candrāpīḍa”

In the eighth century, Tibet was the dominant power north of the Himalayas and, on the other hand, Tang China was jostling to increase its influence in the region. As part of a peace treaty signed between the Tang court and the Tibetans in 707, Princess Jincheng was given in marriage to the Tibetan emperor Tridé Tsuktsen (Tibetan: ཁྲི་ལྡེ་གཙུག་བཙན, r. 704–755 CE). The princess arrived in 710 as a twelve-year old, but was extremely unhappy in her marriage. In 723, she asked for asylum in Kashmir in a letter sent through two Chinese envoys saying, “You are friendly toward China; I wish to leave [Tibet] and surrender to you. Are you willing to accept me?” The Kashmiri king, Tārāpīḍa, sent back a message saying: “Princess, do come here and we will do our utmost to attend [to your needs].”

The intermediary in this exchange was the king of Zābulistān (southern Afghanistan) and a military alliance between him and Kashmir was proposed to counter any Tibetan attack. The Tang Emperor Xuanzong approved of this plan.

The Princess’s plan for asylum in Kashmir, however, never materialized, perhaps due to Tārāpīḍa’s death shortly after he had received the secret communication. Was he killed by Tibetan agents, we don’t know? Princess Jincheng stayed on as empress consort of Tibet although she was to die young in 739 at the age of forty-one

Lalitāditya’s campaigns according to Kalhaṇa

Kalhaṇa describes Lalitāditya as one who spent most of his life in military expeditions. He gives the following account of his campaigns:

Lalitāditya invaded the Antarvedi country, whose capital was located at Gadhipura (between Ganga and Yamuna, Kanyakubja or Kannauj), and where the king was Yashovarman, who was known for a glittering court that included the poet Vākpatirāja, famous for the Prakrit epic poem Gauḍavaho, and the dramatist Bhavabhūti, rated by some as an equal to Kālidāsa and author of plays such as Mālatī-Mādhava.

After initial skirmishes, Yashovarman offered a peace treaty, drawing up a document titled “The treaty of Yashovarman and Lalitāditya”. Lalitāditya’s foreign minister, Mitrasharman, objected to this title, insisting that Lalitāditya’s name be first in the document. Lalitāditya, in agreement with Mitrasharman’s advice, broke off the peace negotiations, resumed the battle and soundly defeated Yashovarman.

Lalitāditya’s invasion of Kannauj has been dated to August 733 CE, based on a reference in the Gauḍavaho to an inauspicious solar eclipse as an allusion to Yashovarman’s defeat. It is accepted that Lalitāditya conquered Punjab, Afghanistan, and western part of the Central Asian highlands before embarking upon his campaign in central India. The idea of Lalitāditya’s conquest of Afghanistan before 730 CE is based on the presence of a gigantic gilt copper Buddha statue beside Lalitāditya’s chaitya at Parihāsapura that appears to be inspired by the Bamiyan Buddha statue.

Furthermore, before Lalitāditya, Afghanistan was controlled by Turkic Shahi kings who were under nominal Chinese control after the fall of the Sasanian Empire. But after Lalitāditya, Afghanistan came under the control of the Hindu Shahi dynasty and Shahi princes served as his ministers after he reorganized the administration.

Lalitāditya instituted five new offices, in addition to the eighteen that were part of the tradition, indicating attention to details, which appear important in governance in a state of continual war. These bore the designations: office of high chamberlain, chief minister of foreign affairs, chief master of the horse, high keeper of the treasury, and chief executive officer (mahāsādhanabhāga).

According to the historian Hermann Goetz [2], Lalitāditya conquered present-day Bihar, Bengal and Odisha by 735–736 CE, and he marched to Gauḍa (Bengal) where he defeated the Later Gupta ruler Jivitagupta, and then advanced up to the Bay of Bengal through present-day Odisha.

Next in his digvijaya was the southern region. The sovereign of Dakshinapatha at this time was a Karṇāṭa queen named Raṭṭā. She allowed his army (perhaps as an ally) to go on to Kaveri River further south and then wheel his army to Malaya mountains (Chandanādri, Chanderi ?) to Avanti and then to Dvārakā on the Western Sea. He proceeded from Avanti to Uttarapatha (the northern region), where he defeated several kings, returning to Kashmir with immense wealth obtained from his conquests.

It has been estimated that the march to Kanyakubja began in 733 CE, with return to Kashmir in 747 CE. This period of 14 years is longer than the 11-year military campaign of Alexander.

Other accounts

Lalitāditya’s campaign against Yashovarman is understandable as the two kings were immediate neighbors: Lalitāditya’s empire extended up to present-day Punjab in the south-east, while Yashovarman’s north-eastern frontier included parts of present-day Haryana. The discovery of coins bearing the legend Śri-Pratāpa (Lalitāditya’s father) in present-day Uttar Pradesh is considered evidence in support of his campaign. Abhinavagupta’s ancestor Atrigupta, a scholar who originally lived in Yashovarman’s territory, was brought to Kashmir by Lalitāditya.

The Kārkoṭa kingdom had peaceful relations with Turkic neighbors in Afghanistan as evidenced by the story about Princess Jincheng and the attempted intersession by the king of Zābulistān. The friendly relations with western kingdoms made it possible for Lalitāditya to leave Kashmir and lead troops to central and eastern India.

Evidence for Lalitāditya’s military domination of the Turkic kingdoms in the Hindukush region is regarding his Tokharian minister called Chankuna, who joined Lalitāditya’s court. In later years, Chankuna was to support many monasteries in the region and build a great monument called Chankunavihāra.

Lalitāditya and the Tang Empire

The first few decades of the eighth century were extremely fluid in the history of the Hindukush-Pamir region. From the west, Turkic forces had made significant inroads and the Tibetans asserted their power by occupying strategic locations in the area. From further northeast, the Tang court tried to defend its garrisons in the Taklamakan, which were under pressure from the Tibetans, while trying to extend its western borders. Taking the Tibetans as a serious threat to its vassals in the region, the Tang court established diplomatic relations with kingdoms located in the southern Hindukush region.

This explains the friendly relations between the Tang emperor of China and Lalitāditya. It appears that Lalitāditya saw the Tibetan empire as the greater threat and formed strategic alliance with the Tang Empire.

In 733, Lalitāditya wrote to the Chinese that he, together with an ally in central India, had defeated the Tibetans in north India. He now offered military help to the Chinese to reduce the sway of Tibet in the north and also supply of provisions to an army even as large as 200,000 strong. In 737, Little Palūr (Gilgit valley) capitulated to the Tibetans. In order to secure their position in the region, the Tibetans gave Princess Khri-ma-lod in marriage to Sushilizhi, the pro-Tibetan leader of Little Palūr. The Tang forces and Lalitāditya, with his formidable cavalry and infantry, continued to battle the Tibetans for control of the region and after three-failed attempts captured it in 747 CE.

Two years later (in 749 CE), the Tang court was visited by an envoy from Tokharistan (Bactria), with a request that it to renew its alliance with Kashmir for a campaign against Tibet’s ally Kashgar. The Chinese acted on the envoy’s recommendation and sent precious gifts to Lalitāditya. The next year Kashgar in Xinjiang was conquered by Tang general Gao Xianzhi and Lalitāditya’s forces. Considering the manner in which the Chinese approached Lalitāditya for support, this could be seen as an extension of Kashmir’s dominions.

The Tibetan invasion of Kashmir in 747 by Emperor Tridé Tsuktsen forced Lalitāditya to return to the Himalayas. He repelled the Tibetans, and invaded the Tarim Basin, and appears to have conquered the kingdoms of Kucha and Turfan. The Turkic kingdom of Tukharistan and the Darad kingdom in the Kishanganga valley was also invaded.

Kalhaṇa’s account also speaks of Lalitāditya’s victory over a kingdom ruled by women (strī-rājya) [3]. The background to this is a mention by Xuanzang of a “Land of Gold”, Suvarṇagotra, that was ruled by women where the male king had no authority and all affairs were directed by the queen: “The men manage the wars and sow the land, that is all.” This strī-rājya mentioned by Kalhaṇa appears to be the Shigar valley of Baltistan, famous for gold-washing and as temporary home of migrants arriving from the north as described in the Buddhist Inquiry of Vimalaprabhā.

It is claimed that the threat of advancing Muslim armies made it easy for Lalitāditya to absorb the neighboring Turkic kingdoms and in this he was aided by the superior Sasanian and Chinese military technologies acquired from the vanquished Turkic kingdoms. It was this “modernized army” of Lalitāditya that mounted successful attacks on rest of India.

South and West India

The name “Raṭṭa” in Kalhaṇa’s account appears to be a reference to the Rāṣṭrakūṭas, who ruled the Karṇāṭa region. Goetz identified Kalhaṇa’s Queen Raṭṭa with Bhavagana, who was a wife of the Raṣṭrakūṭa king Indra I. He speculates that she acted as a queen regent for her son Dantidurga after Indra’s death, but her rule was threatened by her brother-in-law Krishna I. As a result, she appealed to Lalitāditya for help, who arriving in Deccan fought on her side.

Bhavagana was a Chalukya princess before marriage, and therefore, her Chalukya relatives could have allowed Lalitāditya to pass through northern Deccan, enabling him to easily invade the territory controlled by Krishna.

Goetz identified Kalhaṇa’s “Mummuni” with the contemporary Shīlahāra ruler of Konkan. Although no Shīlahāra king by this name is known, there was an 11th-century Shīlahāra king with the same name and it is possible the Kalhaṇa erroneously used the name of a king that was closer to his times.

Kalhaṇa mentions that Kayya, the king of Lāṭa (south Gujarat), built a temple in Kashmir during Lalitāditya’s reign. Goetz identifies Kayya with the Rāṣṭrakūṭa Karka, who succeeded the Chālukyas in Southern Gujarat, and whose name occurs in the Āntroli-Chhāroli grant inscription of 757.

According to Goetz, Lalitāditya invaded Kathiawar (in present-day Gujarat) between 740 and 746 CE. By this time, the local Maitraka kings had already been subjugated by the Chālukyas, which would have allowed Lalitāditya to establish his hegemony in the region [4].

Return to Kashmir

Hermann Goetz speculated that the legendary Guhila ruler Bappa Rawal of Chittorgarh served Lalitāditya as a vassal, and died fighting in the Kashmiri king’s Central Asian campaigns. Goetz goes on to connect Lalitāditya to the mythological Agnikula legend, according to which some later regional dynasties originated from a fire pit during a sacrificial ceremony at Mount Abu.

After returning to Kashmir, Lalitāditya not only repulsed the Tibetans but also invaded the Tarim Basin through Sikatā-sindhu (Ocean of Sand) and marched to Kucha and Turfan after the Tang power had declined as a result of the An Lushan Rebellion.

There are many versions of Lalitāditya’s death and they all are about a military expedition in the northern lands. In one version, he perished due to excessive snow in a northern land called “Āryānaka”. In another version, his army annihilated and his way blocked on a difficult mountainous route, the “great conqueror burned himself on a pyre with his ministers and generals.”

Notes

- The Kārkoṭas were an old Naga family of Kashmir.

- Hermann Goetz, “The Conquest of Northern and Western India by Lalitāditya -Muktapida of Kashmir,” in Studies in the History and Art of Kashmir and the Indian Himalaya, ed. Hermann Goetz. Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden(1969)

- Karl Jettmar, The Paṭolas, their Governors and their Successors. In Antiquities of Northern Pakistan, vol. 2. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz (1993)

- Andre Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. Brill Academic (2002)

Continue reading...