S

Subhash Kak

Guest

Registration of Christian boys for the devshirme blood-tax, painting 1588.

This essay is about some fascinating parallels in the practice of slavery during the medieval period in India and Turkey. Slavery became an essential part of life for the intrusive ruling class in both places to find workers, servants, and soldiers.

Since the available manpower in support of the invaders camped in cities was insufficient, religious law came in handy. Non-Arabs were permitted to be enslaved by law and these slaves could be used to bolster the army, to recruit for the harem, workers, and as servants in households. Theoretically, the slave could look to advancement and future freedom and the possibility of rising to the highest levels, as general and ruler, or even as queen for female slaves.

In many tribes and cultures of Central Asia from where the Turks originated, inheritance of power was not defined by primogeniture (eldest son as heir). The deceased sovereign’s sons and brothers were expected to fight it out to decide who was most fit to rule.

The “law of fratricide” was promulgated by Mehmed II in the middle of the 15th century. He proclaimed: “Two sultans cannot live in the same country. If any of my sons (shahzade) ascend the throne, it is acceptable for him to kill his brothers for the common benefit of the people (nizam-i alem). The majority of the ulama have approved this.” It is estimated that this law resulted in the deaths of at least 80 members of the Ottoman royal family over a period of 150 years.

The prince had to be ever watchful and form alliances with powerful people in the court and be ruthless enough to have his brothers murdered before they killed him. The most sensational case is that of Mehmet III who, upon claiming the throne, summoned his 19 brothers and half-brothers (four adults and fifteen children) to the palace, reassuring them that they were invited for a circumcision ceremony and had nothing to fear.

One by one, the princes were taken to an adjacent room, only to be strangled to death by Mehmed’s four mute-and-deaf executioners. According to Ottoman law, the splitting of royal blood was forbidden; hence, the princes were strangled with silken cords.In Mughal India, there was likewise much fratricide, as in Aurangzeb murdering his three brothers.

Since for religious reasons, women were segregated in the harem so that random men may not see them, eunuchs were needed to guard them. The girls in the harem were often abducted by slavers from distant lands. Some eunuch slaves were to rise high in administration beyond working within the harems.

Slavery as a system was based on economic and political needs of the ruling elite within the moral code of the ruling elite. To satisfy the demand, the supply could be from far-off places if trading networks made that possible.

Ghilman and Mamluks

The Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258) recruited slave soldiers (sing. ghulām, pl. ghilmān) from the Turkish tribes from Central Asia, or prisoners of war from conquered regions. These soldiers were excellent horse riders and fighters. and they were recruited into the Sultan’s personal guard.

The ghilman became powerful, and there were riots against them in Baghdad in 836. The ghilman were part of revolts of their own and during the 860s they killed four caliphs. A ghulam could earn his freedom through dedicated service. Some of them became the de facto rulers of the caliphate. The ghilman paved the way for the Ghaznavid Empire and the rule of Mahmud of Ghazni.

The Mamluks (“one who is owned”) were enslaved mercenaries, slave-soldiers, and freed slaves, who would offer their services to whoever controlled the reins of power. The Mamluks ruled at first from behind the scenes for years but at the end of the Ayyubid dynasty in Egypt, they took control and made themselves masters of the empire as the Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517).

Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526)

The Delhi Sultanate started off as a Mamluk dynasty (1206–1290). The Indian economy was mostly decentralized with self-sufficient village communities. The Turkish and Afghan invaders, being relatively few, needed to live in cities where they could defend themselves, and from where they could project power. The economy of the Delhi Sultanate depended on military expeditions to the scattered Hindu kingdoms and their agrarian lands. Theirs was a war economy of conquest in which slaves played an important role. One measure of the success of a military campaign was the number of captives who could be enslaved.

The writ of Delhi Sultanate authority did not exceed beyond the major cities in northern India. It has been estimated that the population of medieval India was in the range of 100–140 million, whereas the invading Muslims normally confined to cities or fortifications in the rural areas were only several hundred thousand. The garrisons included a huge number of slaves that exceeded the number of Afghans and Turks. During the period of Firuz Shah (r. 1351–1388), Delhi with a population of about 400,000 had about 180,000 slaves.

The acquisition of slaves happened in various ways: through war in which the defeated army was enslaved, raids into the countryside to abduct girls and women, servants, artisans and craftsmen, and debt defaulting. Enslavement of the defeated army served the purpose of preventing the defeated soldiers from regrouping and becoming rebels.

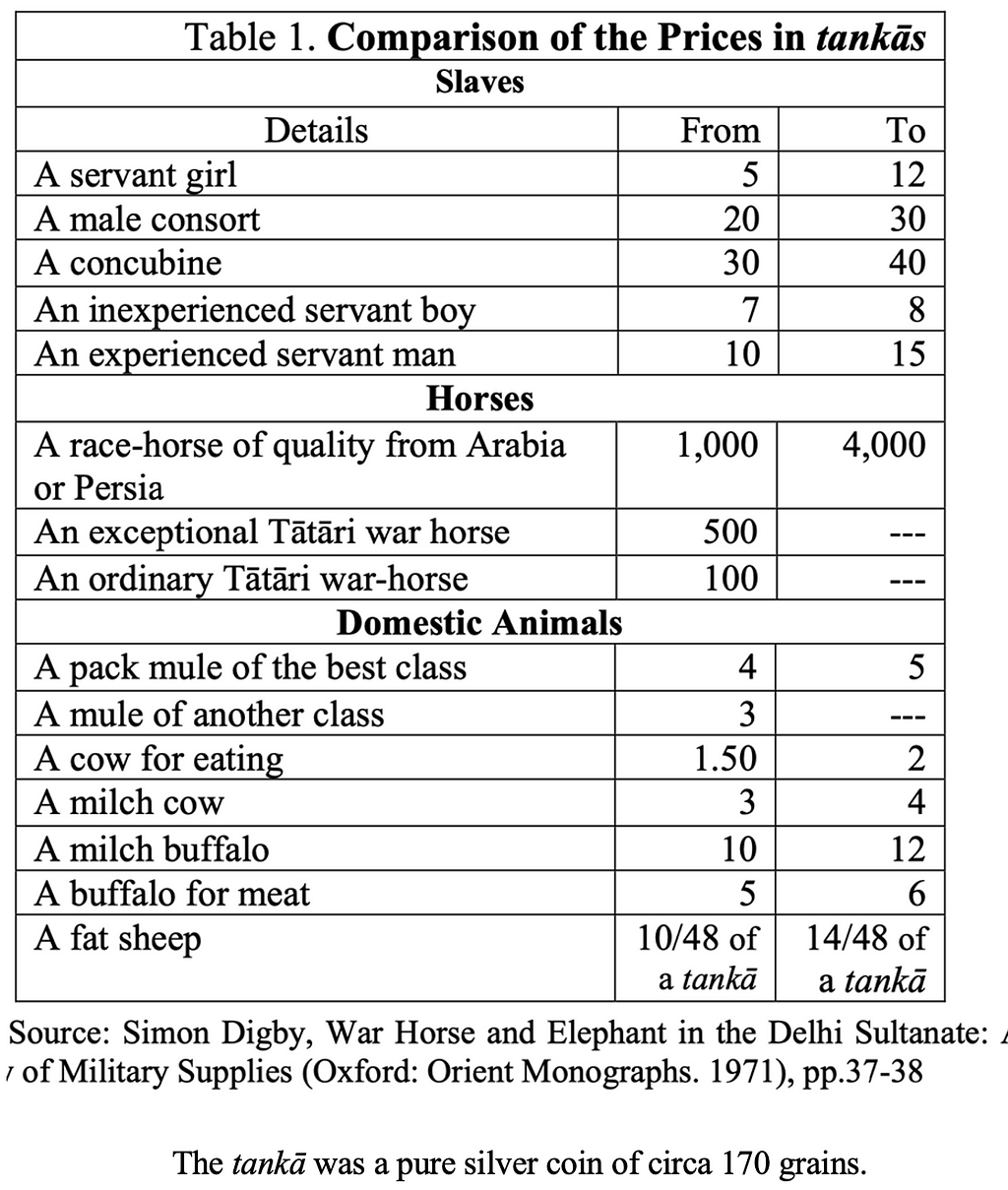

The Table below provides relatives prices of slaves, horses, and animals.

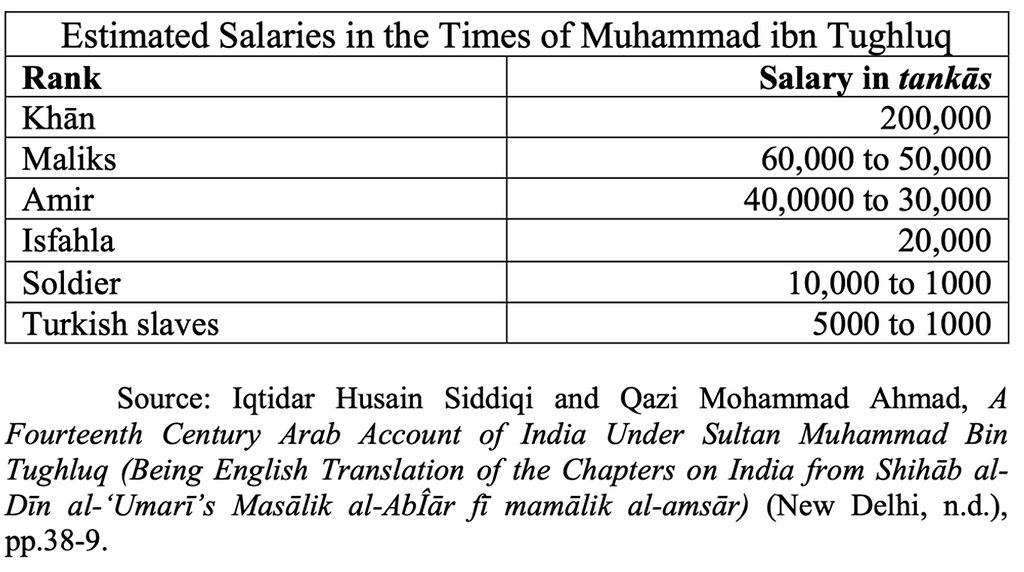

The talented and well-trained slaves were expensive. For instance, Iltutmish, the third sultan of the Delhi Sultanate who started off as a slave, was purchased for one hundred thousand tankā. The slave system also required a huge gap in the income between the slaveholders and slaves. The next table shows that the income of the top aristocrats was over 10,000 times the price of a slave-girl.

To provide an idea of the importance of slavery, note that Qutb ud-Din Aibak in his military operation in Gujrat in 1195 captured 20,000 slaves, and seven years later, in the Kalinjar campaign he had another 50,000. In 1380 Firuz Shah marched to Katehar to subdue a rebellious king and enslaved 23,000. After retaining 40,000 in his court, the extra slaves were shipped out to regional subordinate officers and governors.

Eunuchs

Eunuch slaves were employed for the care and surveillance of the females of the harem. They were usually bought as boys and castrated. Since they couldn’t have children of their own, it was felt they would be less likely to siphon off money.

Malik Kafur is believed to have been the lover of Alauddin Khalji. During the final days of Alauddin’s reign, when he was sick, Kafur allowed no one to see the sultan, and became the de facto ruler of the Sultanate.

According to the chronicler Ziauddin Barani (1285–1357): “In those four or five years when the Sultan was losing his memory and his senses, he had fallen deeply and madly in love with the Malik Naib. He had entrusted the responsibility of the government and the control of the servants to this useless, ungrateful, ingratiate, sodomite.”

Khusrau Khan became a gay lover of Alauddin’s son Mubarak Shah, who was to ascend the throne in 1316. In 1320, Khusrau led a revolt against Mubarak Shah and killed him, and ruled as Sultan for three months.

Muhammad ibn Tughluq’s slaves fought in front of his elephants. When the Sultan moved from one palace to the other, there were 12,000 slaves around him and all of them were on foot. He was also accompanied by ten thousand eunuchs. The eunuchs also served as spies on other nobles.

Devshirme system

The Devshirme, a blood-tax levied on the Christian territories, was a variation to the Ghilman system. Estimated to have begun in the late 14th century, in which Christian boys (usually between the ages of 6 and 14, mainly from the Balkans) were subjected to forced circumcision and conversion to Islam.

The Turkish soldiers would scour their regions every five years for the strongest sons of the sultan’s Christian subjects. Their aim was to create a group that would be loyal to the Sultan rather than to their own families. The boys were taken to Istanbul and placed with Muslim families or in schools. They were subjected to severe discipline and were prohibited from growing a beard.

Many became soldiers and army officers, including the elite Janissary corps, the sultan’s personal troops. Others became government ministers, provincial governors, and even grand viziers, the highest office except for the sultan. The Devshirme system slowly declined in the 17th century.

Janissaries

The formation of the Janissaries (Turkish: yeŋiçeri, “new soldier”) is traced to around 1365, during the rule of Orhan’s son Murad I, the first sultan of the Ottoman Empire. The Janissaries became the first Ottoman standing army replacing forces that mostly consisted of tribal warriors (ghazis) whose loyalty and morale were not always guaranteed.

Legally slaves of the sultan, they served over the centuries as bowmen, crossbowmen, and musketeers. They were distinguished from the main body of the army, which was made up of cavalrymen (sipahis) drawn from the freeborn retinues of provincial officials and notables.

They were the first modern standing army, and were the first regular army to wear unique uniforms, to be paid regular salaries for their service, to march to music (the mehter), to live in barracks and to make extensive use of firearms. They were famous for their distinctive marching style and headgear; their special military bands inspired military bands all over Europe.

Forbidden to marry before the age of 40 or engage in trade, their complete loyalty to the Sultan was expected. The janissaries were a formidable military unit in the early centuries, but as Western Europe modernized its military organization and technology, the janissaries resisted change. By the time the janissaries were suppressed, it was too late for Ottoman military power to catch up with the West. The corps was abolished by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826 in the Auspicious Incident, in which 6,000 or more were executed.

Osman II in a procession of Janissaries and guards

Children are recruited for the janissaries in the Balkans

Women slaves and consorts

Another part of the royal household ruled behind the scenes and sometimes became even more powerful than the grand vizier. Ottoman slavers would regularly kidnap young girls from central Europe to be sold into concubinage. Some of them would find their way into the harem of the Ottoman sultan, where they would vie to find favor with their master. It was possible for a young girl — -separated from her family and taken as a captive in a faraway land — — who was sold in the most depraved of circumstances, to rise to power and become the sultan valide, the queen mother, the second most powerful individual in the empire.

The most famous example was Roxelana. Originally from Russia, she entered the harem of Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566) where her name was changed to Hürrem, and she rose through the ranks and became the favourite wife of the sultan. Breaking Ottoman tradition, Suleiman married Hürrem, making her his legal wife receiving the title Haseki Sultan (Imperial Consort). It is believed that she convinced Suleiman to have his son Mustafa (born to a rival queen and the eldest shahzade) killed so that her own son Selim II would ascend to the throne. Selim II’s own imperial consort, Nurbanu Sultan, was herself abducted from either Venice or Greece according to different accounts, and she was also to become sultan valide.

Slavery in Khiva

In the period from 17th to19th centuries, Khiva just north of Afghanistan prospered from its slave-market. During the first half of the 19th century alone, some one million Persians and an unknown number of Russians, were transported to Central Asian khanates. When the Russian troops took Khanate of Bukhara in 1898, its population was 1.2 million together with 200,000 Persian slaves.

The slaves were supplied by Turkmen and Kazakhs who took hostages during kidnaping raids. The raids would take place at night for settled places or at sunrise for caravans. The newly captured slaves were dragged through the desert, hands tied and ropes around the necks, to the bazaars of Khiva or Bukhara.

Iranian Shῑ’ites would constitute most Central Asia’s enslaved people for three centuries, for the Sunni clerics had declared the Shīʿa as heretics and, therefore, legally enslavable.

A significant first-hand account of slave-dealing comes from the Kashmiri adventurer and author, Mohan Lal Zutshi, who played an important role in the first Anglo-Afghan War of 1838–1842 and authored the biography of Dost Mohammad Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan in Kabul, which is a primary source on the war. As an aide to the explorer Alexander Burnes, he visited several slave-bazars in the Khanate of Bukhara.

He writes in his book Travels in the Panjab, Afghanistan, and Turkistan, to Balk, Bokhara, and Herat; and a visit to Great Britain and Germany (London: W. H. Allen, 1846) of a visit to a town called Qarshi:

On my return from the bazar, I asked my companion to shew me the house of a slave-dealer; so I was conducted through numerous hot streets, and after a short walk, I got into the caravansarae where the merchant resided. He received me with courtesy and sent for three women from the room next to his own. They sat unveiled, and their master asked me which of the three I liked the best. I pretended to select the younger one; she had regular features and most agreeable manners, her stature was elegant, and her personal attractions great. On my choosing her, the others retired to their lodgings, and she followed them, but sat in a separate room guarded by an old slave. The merchant told me to go to her, speak to and content her. After a good deal of conversation, she felt pleased with my choice; but told me to swear not to sell her again. She was thirteen years of age, and an inhabitant of Chatrar, a place near Badakhshan. She said that she belonged to a large family, and had been carried off by the ruler of the country, who reduced her to slavery. Her eyes filled with tears, and she asked me to release her soon from the hands of the oppressive Uzbeg. As my object was only to examine the feelings of the slave-dealer, and also to gratify my curiosity, and not to purchase her, I came back to my camp without bidding farewell to the merchant.

Continue reading...